The Women Impressionists Buried in History

“Only a woman has the right to rigorously practice the Impressionist system,” Téodor de Wyzewa wrote in an 1891 article. The art critic made the claim that the French Impressionist style celebrated superficiality in a way that was intrinsical—and unflatteringly—feminine. “She alone,” he continued, “can limit her effort to the translation of impressions.” Other art critics joined de Wyzewa’s chorus, belittling the Impressionists for a new art form they felt suggested the limited capabilities of women, not the sharpened skills of men.

An independent group of artists that staged exhibitions outside the established Paris salon system, the Impressionists were indeed radical, and not easy for critics to love. They prioritized studying the effects of light in small-format works predominantly painted en plein air with un-blended colors rendered in soft, broken brushstrokes. Instead of aspiring toward monumental history painting—then considered the pinnacle of artistic achievement—the Impressionists, with their countless views of contemporary Paris, argued that modern life was itself a worthy subject.

Impressionism is not only Monet, Renoir, and Degas. There were women Impressionists who exhibited works that were as innovative as those of their male counterparts. As they shaped their unique careers and artistic styles, the painters negotiated not only personal challenges but also those posed by the conventional ideas of acceptable behavior for women of their time.

Berther Morisot

Impressionist Berthe Morisot studied with Barbizon School painter Camille Corot who taught her how to paint en plein air. Like Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt, the other well-known female painters of her generation, Morisot avoided the urban street scenes and nude figures that male Impressionists depicted. Instead, she painted her daily experiences and observations, focusing on boating scenes, garden settings, domestic interiors, and portraits of family and friends that convey the comfort and intimacy of family life. She exhibited her work alongside Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, and married painter Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène.

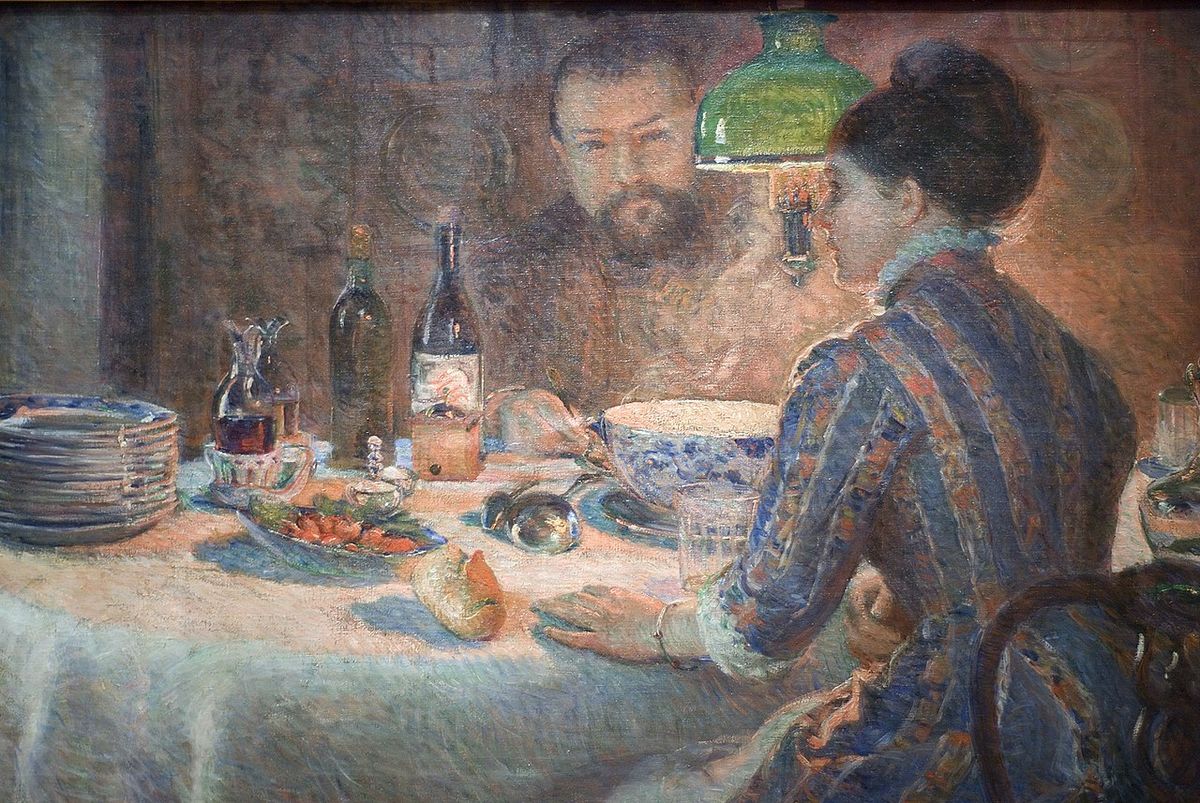

Marie Bracquemond

Marie Bracquemond (December 1, 1840 – January 17, 1916) was a French Impressionist artist, who was described retrospectively by Henri Focillon in 1928 as one of "les trois grandes dames" of Impressionism alongside Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Her frequent omission from books on artists is sometimes attributed to the efforts of her husband, Félix Bracquemond. Félix respected his wife's talents as an artist but disagreed fervently with her adaptation of Impressionist techniques, in particular, her use of color.

Louise Catherine Breslau

Swiss artist Louise Catherine Breslau first began drawing as a means of survival, an attempt to stave off boredom during the childhood years she spent at a lakeside convent recovering from asthma. The diversion soon became her primary focus, and once old enough, she moved to Paris to study art. Within a couple of years, Breslau succeeded in exhibiting a self-portrait at the Paris salon. Breslau showed regularly in the time-honored salon but adapted some habits of the Impressionists: She painted en plein air in Brittany (a popular artist destination) and used a deft, sketchy brushstroke. Breslau found enough success to open her own studio, which was largely supported by her portrait commissions.

Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt is widely acclaimed for her intimate scenes of mothers and children, such as Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child (1880), that are painted with quick brushstrokes in a pastel palette. Invited in 1877 by her friend and mentor Edgar Degas, Cassatt was one of three women—and the only American—to join a group of artists later known as the Impressionists, which included Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro. Influenced by the Japanese prints she collected, Cassatt developed a refined drawing style that blended European and Asian effects, increasingly creating figural compositions, like The Letter (1890), with flattened forms and harmonious color combinations.

Eva Gonzales

Born into a creative Parisian family (her father was a novelist, her mother a musician), Eva Gonzalès and her sister Jeanne were always encouraged to paint. As a teenager in Paris, she trained with painter Charles Joshua Chaplin (who was also, coincidentally, one of Cassatt’s first French instructors), before eventually moving on to Édouard Manet’s studio, where she was his only formal student—and an occasional model. Gonzalès never showed with the Impressionists, preferring the recognition that came with having her work accepted for exhibition at the prestigious and traditional salon (a feat she achieved in 1879). Still, her pastel palette and loose style have always linked her with the Impressionists, and she knew a few of them, including Berthe Morisot and Paul Cézanne, personally.

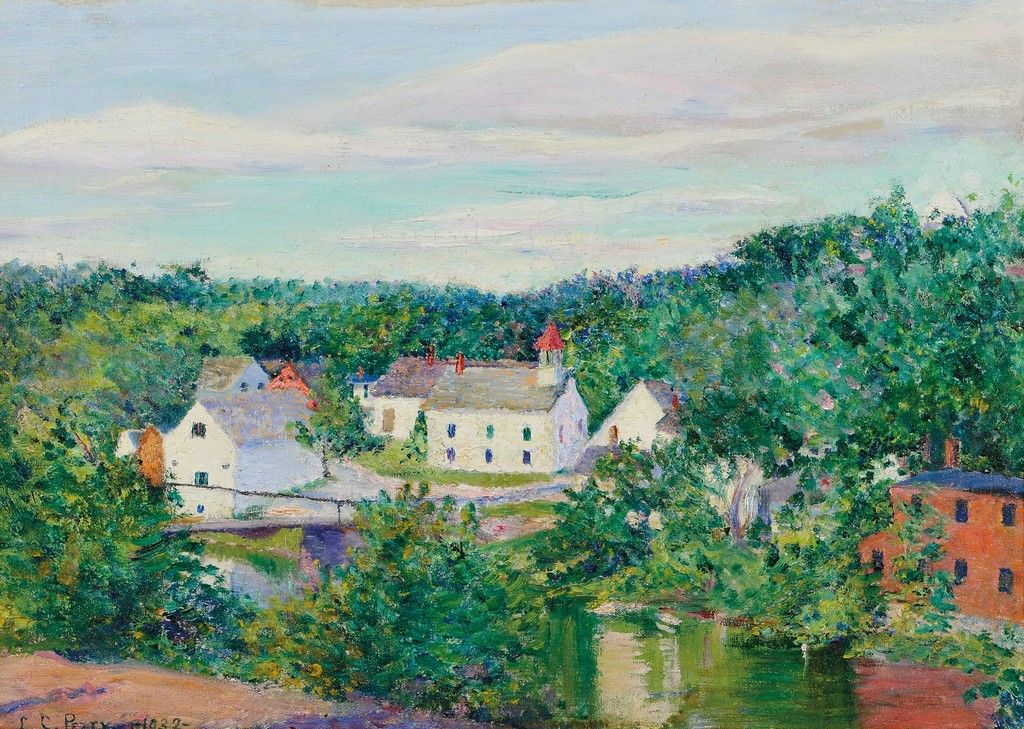

Lilla Cabot Perry

Lilla Cabot Perry drew as a child, but only learned to paint at age 36, after the births of her three daughters. Painting quickly became a daily practice for the next 50 years of her life. Born and raised in Boston, Perry’s wealth enabled her to live and study in Paris, family in tow. In France, she developed a love for the Impressionists, inspiring her to deliver lectures about the artistic circle back home and exhibit her personal collection of works by Claude Monet.

Cecilia Beaux

Passionate and ambitious, Cecilia Beaux renounced marriage, motherhood, and docility to become one of the most distinguished portrait painters in America, in the vein of John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt. A committed professional, Beaux came to prominence in 1899 for her penetrating, exquisitely rendered portraits of the American upper classes and was awarded membership to the male-dominated National Academy. She was best known for her portraits of women and children and painted the wife and daughter of American President Teddy Roosevelt in the White House.

Post a comment